Understanding BMI

Written by Arbitrage • 2025-07-29 00:00:00

Body Mass Index (BMI) has long been used as a quick and standardized way to assess whether someone falls within a healthy weight range. Although BMI remains common in medical offices and public health campaigns, it has increasingly been scrutinized for its limitations and potential harms. Obesity is estimated to affect more than 1 billion people worldwide. In the United States, about 40% of adults have obesity, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). As our understanding of health and body composition evolves, many medical professionals are questioning whether BMI should still be the default tool for evaluating wellness.

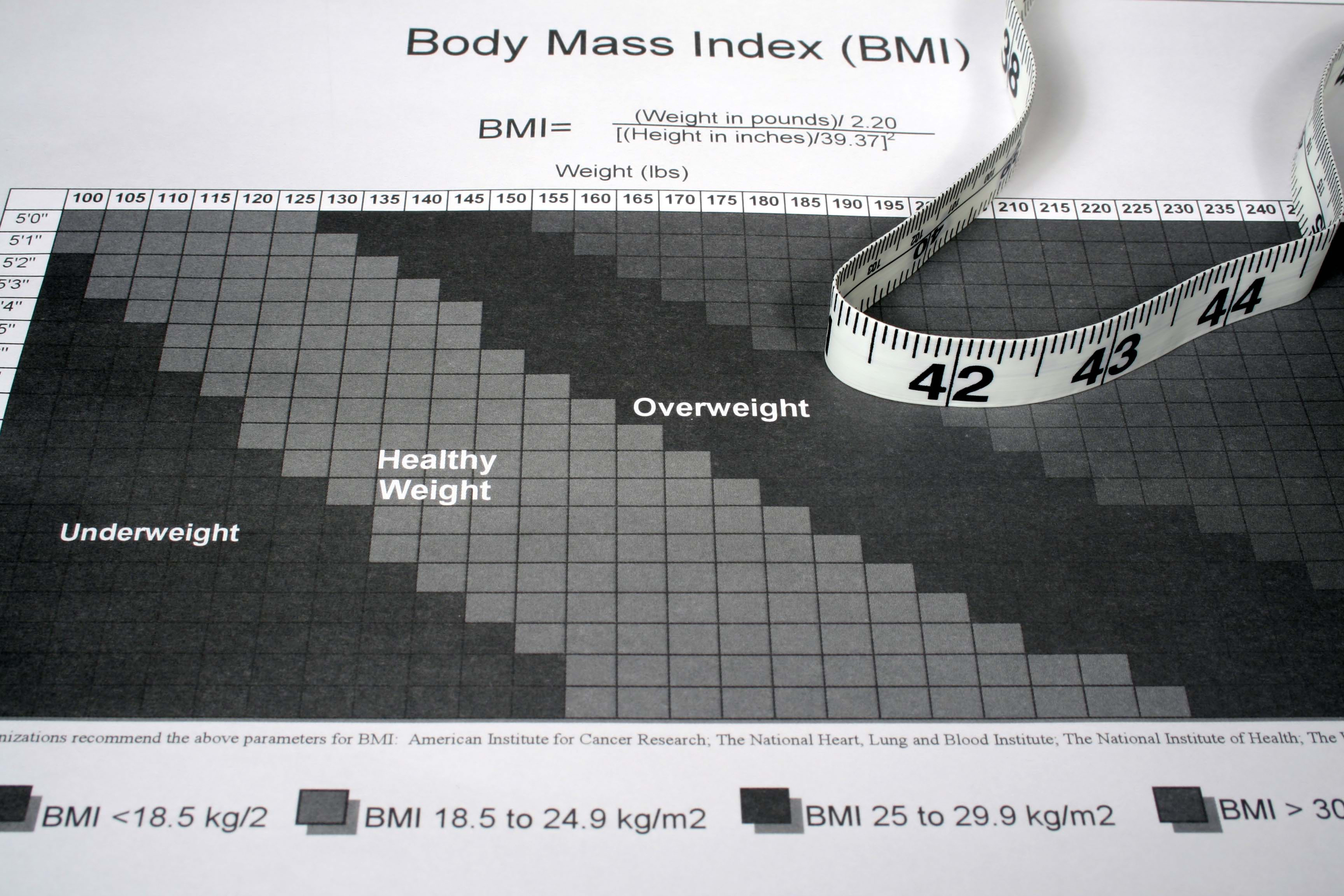

The concept of BMI dates back to the 1830s when Belgian mathematician and statistician Adolphe Quetelet developed what he called the "Quetelet Index." His goal wasn't to measure individual health, but rather to study trends in the "average man" for population-level statistics. It wasn't until the 1970s that American physiologist Ancel Keys renamed it the Body Mass Index and then proposed it as a useful tool for measuring body fatness in large-scale epidemiological studies. From there, BMI quickly became embedded in modern health assessments due to its simplicity: divide your weight by the square of your height. (The National Institutes of Health (NIH) offers a free BMI calculator.)

Today, BMI is widely used by doctors, insurance companies, and health organizations to classify individuals into categories such as underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese. These classifications are tied to increased risks for various health conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, kidney and liver disease, and certain cancers. However, critics argue that BMI is too blunt an instrument to capture the complexities of human health.

One of the main issues with BMI is that it doesn't differentiate between muscle and fat. Because muscle and bone weigh more than fat, BMI measurements can overestimate the danger for people with a muscular build or a larger frame. Conversely, BMI can underestimate health concerns in older adults and anyone who has lost muscle. Dr. Yoni Freedhoff, an obesity medicine specialist and associate professor at the University of Ottawa, summed it up: "[BMI] is a tool of convenience, not precision."

Another issue is that BMI does not account for age, sex, ethnicity, or genetics - all of which influence body composition and disease risk. Studies have shown that people from different ethnic backgrounds may experience obesity-related health risks at different BMIs. For example, individuals of South Asian descent may face higher risks of diabetes and cardiovascular disease at lower BMI thresholds compared to white populations.

While BMI remains useful at a population level (for example, tracking obesity rates or guiding public health policy), many experts agree it should not be the sole indicator of an individual's health. Alternative tools like waist-to-hip ratios, body fat percentage measurements, and metabolic panels can offer a more nuanced view of a person's overall health. In recent years, even the American Medical Association acknowledged BMI's limitations, stating in 2023 that BMI should not be used as the "sole criterion" for diagnosing obesity. Dr. Arch Mainous III, professor and vice chair of research in community health and family medicine at the University of Florida School of Medicine, said. "[Doctors would] like to use a more direct measurement such as a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan, but those cost too much and are not widely available, so everyone falls back to the indirect measure of BMI." DEXA is the gold standard for body mass analysis - but these machines can cost between $45,000 and $80,000, so patients typically have to travel to a hospital or specialty center to get the scan. The cost to the patient can easily be $400 to $500 per scan, and insurance may or may not cover the scan.

As the medical field continues to move toward more personalized and holistic care, reliance on BMI may fade. "The whole goal of this is to get a more precise definition so that we are targeting the people who actually need the help most," said Dr. David Cummings, an obesity expert at the University of Washington. Until then, it is essential to remember that health cannot be reduced to a single number, and that the path to well-being looks different for every body.