From Gold to Greenbacks: How Bretton Woods Cemented the Dollar’s Reign

Written by Arbitrage • 2025-10-01 00:00:00

In the summer of 1944, with World War II still raging but victory within sight, the global economy was in tatters. Europe was bombed out, Asia was destabilized, and the international monetary system was in chaos. Against this backdrop, representatives from 44 Allied nations gathered at a small resort in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. Their goal: to design a financial system that could stabilize currencies, rebuild economies, and prevent a repeat of the Great Depression.

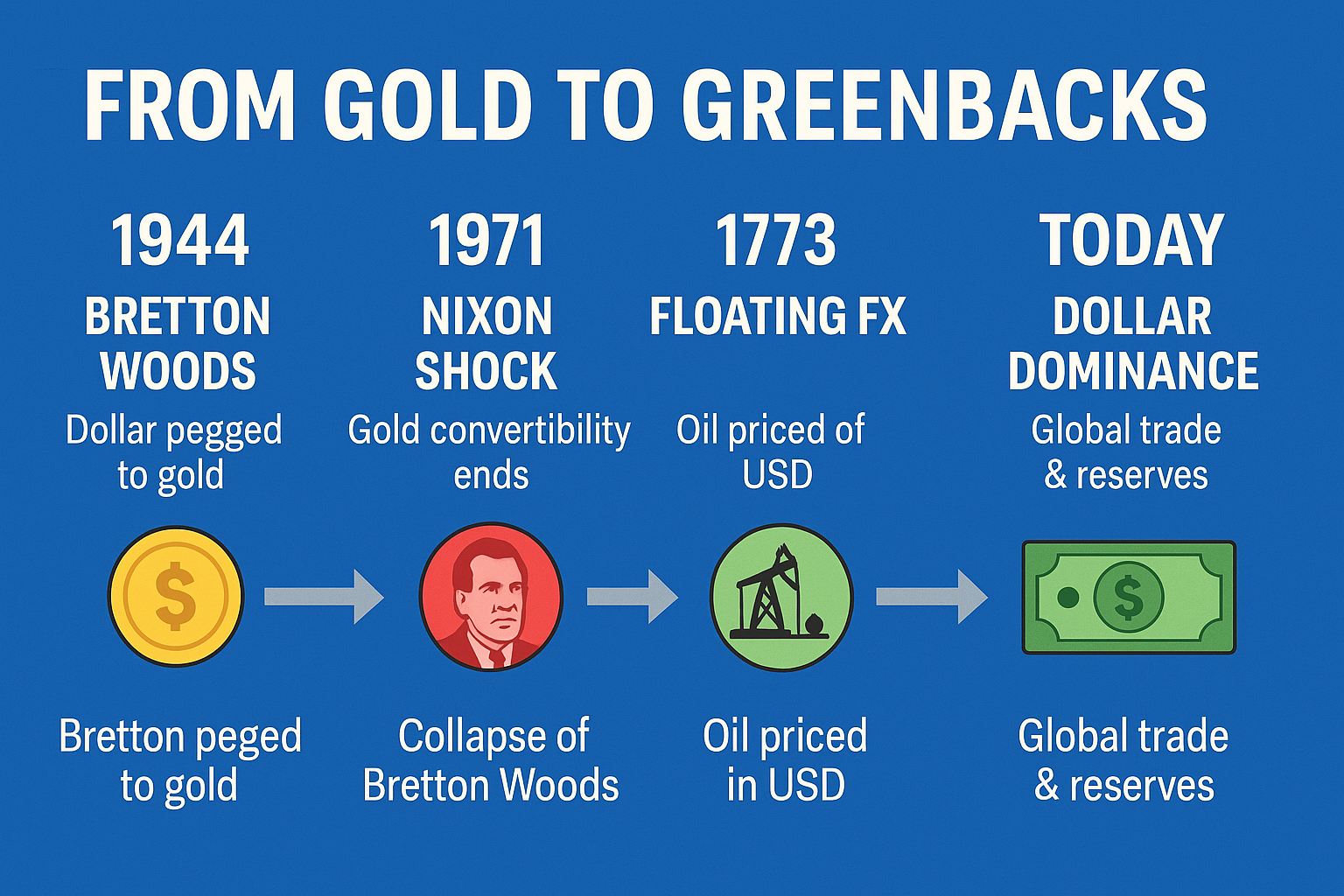

What emerged from that conference didn't just stabilize global finance - it elevated the U.S. dollar to the center of the world's economy. And while Bretton Woods itself eventually collapsed, the dollar's reign survived, bolstered by a new system that linked oil, energy, and global trade directly to the greenback.

Before Bretton Woods: The Gold Standard and Global Uncertainty

Before Bretton Woods, international money was anchored to gold. Currencies were directly convertible into gold, which provided stability but also rigidity. When the Great Depression hit in the 1930s, countries scrambled to devalue their currencies, erect trade barriers, and protect their own economies. The result? "Beggar-thy-neighbor" policies that deepened the depression and destabilized global trade. By the time World War II broke out, the gold standard was effectively dead. The world needed something new - a framework that provided stability, but also flexibility.

The Bretton Woods Conference: Designing a New Order

In July 1944, 730 delegates from 44 nations descended on Bretton Woods. Two men in particular shaped the debate: John Maynard Keynes, representing Britain, and Harry Dexter White, representing the United States. Keynes proposed a new international currency, the "bancor," while White pushed for a system anchored to the U.S. dollar. With the U.S. holding the world's largest gold reserves and emerging as the dominant economic power, White's plan won. The conference created two new institutions:

- The International Monetary Fund (IMF): to lend money to countries facing short-term currency crises.

- The World Bank: to finance reconstruction and long-term development.

But the real innovation was the monetary system itself.

The Dollar at the Center: Gold Exchange Standard

Under Bretton Woods, global currencies would be pegged to the U.S. dollar, and the dollar itself would be convertible into gold at $35 an ounce. This made the dollar "as good as gold." Because the U.S. held roughly two-thirds of the world's gold reserves, other nations were comfortable anchoring their currencies to it. The greenback became the linchpin of global trade and finance.

Dollar Dominance in Practice

The system worked. The postwar boom was fueled by U.S. capital and demand. The Marshall Plan - America's massive program to rebuild Europe - injected dollars into devastated economies. With U.S. industry intact and the dollar backed by gold, countries worldwide trusted and depended on it. By the 1950s and 1960s, the dollar wasn't just the anchor of Bretton Woods; it was the world's primary reserve currency and the unit of account for global trade.

The Cracks Appear: The End of Bretton Woods

But by the 1960s, strains began to show. The U.S. was running persistent trade deficits, spending heavily on the Vietnam War, and financing new social programs at home. Dollars flooded the world, but U.S. gold reserves stayed flat. Foreign leaders (most famously Charles de Gaulle of France) began questioning whether the U.S. could really redeem all those dollars for gold. Countries started demanding gold instead of dollars.

In August 1971, President Richard Nixon ended the dollar's convertibility into gold. Known as the "Nixon Shock," this move effectively killed Bretton Woods. By 1973, the system of fixed exchange rates was gone, replaced by today's floating currency regime. For many countries, the end of Bretton Woods might have meant the end of dollar dominance. But instead, a new system emerged to secure the dollar's role.

The Petrodollar: A New Foundation for Dollar Power

The 1970s brought another crisis: the oil shocks. As OPEC flexed its muscle and oil prices soared, the U.S. struck a strategic deal with Saudi Arabia. The agreement was simple but powerful: oil would be priced exclusively in U.S. dollars, and in return, the U.S. would provide military protection and support to the Saudis.

Soon, other OPEC members followed. This arrangement, known as the Petrodollar system, created guaranteed global demand for dollars. Every nation that needed oil - which meant every nation - needed dollars to buy it. Oil exporters, in turn, recycled their dollar earnings back into U.S. assets, particularly Treasury bonds. This kept U.S. financial markets liquid and interest rates relatively low, fueling further growth. Even without gold, the dollar's role as the backbone of global trade was locked in - now underpinned by energy.

The Dollar's Continued Reign

Today, the U.S. dollar accounts for nearly 60% of global foreign exchange reserves and dominates international trade invoicing. Commodities from oil to wheat are priced in dollars. U.S. Treasury bonds are seen as the safest store of value during times of crisis.

Challenges exist - from the euro, the Chinese yuan, and even digital assets like Bitcoin and stablecoins. But no rival has yet matched the dollar's liquidity, trust, and geopolitical backing.

Conclusion: The Lasting Legacy of Bretton Woods (and Beyond)

Bretton Woods may have collapsed in the early 1970s, but it was the launchpad for the dollar's dominance. First anchored to gold, then reinforced by oil, the greenback became the central pillar of the global financial system.

The lesson is clear: money is never just about economics - it's about power, trust, and strategy. And from Bretton Woods to the Petrodollar, the U.S. has played that game better than anyone else.